Teresa Hedley wrestles with these questions in her memoir, What’s Not Allowed with grace, humility, humour, honesty, wisdom and optimism. She describes her life as it unfolds before and after her middle son is diagnosed with autism. Teresa shares her family journey as they support her son, Erik as he learns how to live in a world being identified as different.

I began reading this story with a basic understanding of autism and some limited experience as an elementary school teacher. As a parent of two sons, I certainly could relate to the worries and trials of parenthood. During my career, I was a continual advocate for children and parents who were trying to make sense of labels, learning and behavioural challenges. The system bureaucracy can be daunting, inflexible and often lacks creativity, especially for children who have been placed within a category. Throughout Teresa’s narrative, I could relate to her experiences as a teacher and parent.

Teresa’s sharing of her family’s autism journey is authentic and courageously detailed. I don’t know many people who not only would be willing to share a multitude of home and school scenarios but would do so from a point of humble, fair, and humorous reflection. In addition, she digs deeper, sharing how both her and her husband’s upbringing molded their perspectives and parenting approaches. It is a wonderful celebration of the power of generational optimism, grit and faith.

In What’s Not Allowed, Teresa provokes us to remove our preconceived notions and definitions, plus, step away from judgement and ask: Is an autism diagnosis a disability or a gift? Through her powerful sharing, we get a sense of what it is like to walk in the shoes of a person having autism and from those supporting and advocating for their diagnosed loved one. We can also see and feel from the accounts of many others, (teachers, friends, therapists, coaches etc) who step beyond their own judgemental egos and see the sparkling gifts that the person with autism shares.

Teresa calls us all to rethink not only how we perceive autism but any label we place on another. She dares us all to ask:

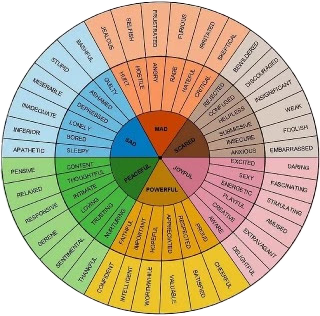

- How are we assessing behaviour, offering prognosis and strategies? Is our approach fair and reasonable? Moreover, does our approach consider the ‘labelled’ person’s perspective or the outsider’?

- How fast do we need to find a solution? Do we prefer to access quick fixes like medication over the patience required to scaffold skill development?

- What do we believe? Do we see growth and possibility, or do we see struggles and failure?

- How far are we willing to have the courage to question professionals?

- Do we want to develop independence, capability and strength or do we want to reinforce dependency and vulnerability?

- What is the difference between codependency and enabling versus loving support and coaching?

Ultimately, I have come away from reading Teresa’s memoir being far more sensitive and aware of how autism has affected my life. As Teresa suggests, the spectrum is probably wider than we realize. She shares Erik’s mindfulness, kindness and acceptance that Erik purely and gracefully presents. Erik is devoid of the judgment ego. She reminds us that since her son was diagnosed 17 years ago, our world has a greater knowledge of autism, and as such, with her advocacy and his developed skills, he has gained great admiration and respect. YET, Teresa reminds us that we still have far more to understand.

Teresa’s story is one for all: educators, parents, grandparents, medical professionals and anyone looking to have a greater understanding of our humanity. It is inspiring, humorous and guiding while offering repeated examples of courage and wise reflection. The journey is packaged in short digestible chapters that will leave you laughing and crying while nodding over the multiple metaphors, analogies, and idioms. What’s Not Allowed has the potential to be an explosive film one day!

Post-read; I am wandering in deep reflection on the topic of autism. I go back to the Greek origins of the word autism, meaning self, then reflect that the reactions that many individuals with autism present when distressed in the present moment are self-soothing behaviours, which would indicate incredible self-awareness and self-care. Is this not what many of us neurotypicals struggle with—self-awareness and self-care? The autistic intuitively know how to self-regulate in a way many find socially awkward or uncomfortable but the neurotypical self-soothe with substances and/or socially acceptable soothing behaviour (which can be highly destructive not only to them but to others). Are those with autism closer to what we all aspire to, being in the present moment? Can we say that autism is authentic, innocent and pure? So, who owns the disability and who has the gift?

You have been called Mother Teresa by your friends. I couldn’t agree more! Thank you, MT for sharing your heartfelt story and teaching me what it means to really have empathy!

Reader, if you need more of a nudge to read this compelling story take a look at Peter Mansbridge’s endorsement!